Sequences 2: Collections

A Collection is Sequence with guarantees that its elements can be iterated through repeatedly, without consuming them, and also allows elements to be accessed by a specified index without needing to iterate to find them.

Lets have a look at Array again. We previously saw that we can iterate through the elements of an array using a for-in loop and each of the elements is supplied by the Iterator for the array.

We can also access a single element in the array by using a zero-offset index for its position;

let array = ["a", "b", "c", "d", "e"]

let firstElement = array[0] // contains "a"

let middleElement = array[2] // contains "c"

This index access is defined in the Collection protocol.

protocol Collection<Element>: Sequence {

subscript(position: Self.Index) -> Self.Element { get }

var startIndex: Self.Index { get }

var endIndex: Self.Index { get } // The 'past the end' index.

func index(after i: Self.Index) -> Self.Index

func formIndex(after i: inout Self.Index)

}

Index

The index of a collection is the value which can be used to efficiently address a single element within the collection.

There are two properties on a collection to define the boundaries of the indices:

startIndex is the index of the first element and endIndex which is the ‘past the end’ index (i.e. it does not correspond to an element in the collection but is the index after that of the final element.

Why, you may wonder, is the endIndex not just the index for the final element? It is general convention and can be seen in c++ and it allows for certain conveniences; if a collection is empty its endIndex will equal its startIndex which allows for the efficient constant-time implementation of the var isEmpty: Bool { get } property. This efficient implementation is why it is always preferable to use the property rather than querying the count to determine if a collection is empty.

The index does not necessarily denote a logical ordered position for the element within a collection. It also does not even denote the way which a developer would access the element. It exists purely for the iterator & subsequence functionality of Collection to allow that element to be efficiently accessed.

Let’s look at Set and Dictionary in the standard library to understand this better.

Set is an unordered collection which can only store unique elements (it cannot contain multiples of the same element). From a developer perspective, an element in a Set does not have a position; it is either in the set or its not. The generic methods to interact with the elements are insert(element), remove(element) and contains(element).

So what does Set use for its index? Well, the actual type is Set.Index and it look as follows:

extension Set {

public struct Index {

internal enum _Variant {

case native(_HashTable.Index)

case cocoa(__CocoaSet.Index)

}

internal var _variant: _Variant

}

}

It has that _variant property which is an enum holding the index for the actual backing store of the set. It can either be backed by a cocoa NSet/CFSet or it can be a native set which is backed by a hash table.

So what is the index of the hash table? Well in a simplified manner it looks as follows:

extension _HashTable {

internal struct Index {

let bucket: Bucket

let age: Int32

internal init(bucket: Bucket, age: Int32) {

self.bucket = bucket

self.age = age

}

}

}

It is pointing to the bucket of the hash table which stores the element allowing it to be found without having to perform the hash on the element to find that bucket.

Dictionary is a unordered key-value store in which allows values/elements to be accessed by use of a hashable key. From the developer perspective that element is accessed though that key. It would seemingly make sense that the Element type for a dictionary is its element and the Index value is the type of the key.

That is not the case however, and there is a hint of that when we look at it being consumed by a for-in loop:

let dictionary = ["a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3, "e": 5]

for (key, element) in dictionary {

// consume key and element

}

The Element is in-fact a tuple which contains both the key and the element. So what is the Index? Well its going to look pretty familiar:

extension Dictionary {

public struct Index {

internal enum _Variant {

case native(_HashTable.Index)

case cocoa(__CocoaDictionary.Index)

}

internal var _variant: _Variant

}

}

Yep, it’s pretty much exactly identical to Set including being backed by the same hash table.

A developer will likely never directly interact with the indices for elements in a dictionary. They exist for allowing the quick access to an element when it is being iterated. It may be developer facing such as the Integer index of an Array or iteration specific like for Dictionary. It is something you can also consider whenever making custom Collections; how can I make the Index to access an element as quickly as possible?

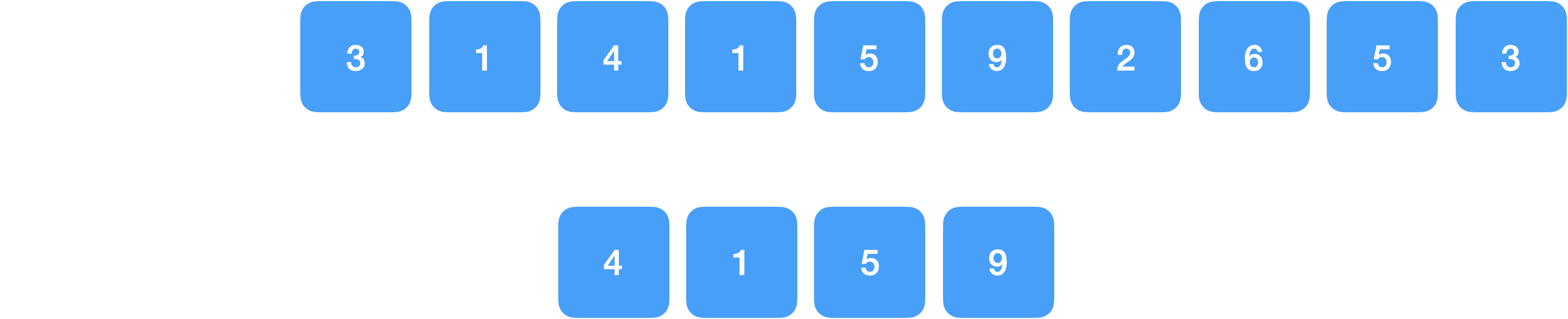

Subsequence

A subsequence is a contiguous subrange of a collection which will use the original collection as its backing store to avoid having to copy the contents into a new collection.

An important thing to note is that the Indices for the elements within a Subsequence exactly match those of the original sequence. It makes sense really, those indices are designed to allow for quickly accessing the elements and the subsequence is backed by the original collection so each of the elements would be accessed by those original indices.

This can cause some confusion for developers though, especially for types which use their indices for element access, such as Array.

The first element of an Array always has the index 0 and developers will often use this to access that first element.

Array does offer the var first: Self.Element? { get } property to access the first element but it does return an optional which will need to be unwrapped to use. definitely safer but sometimes seen as an extra step, especially if the developers knows the array will not be empty.

This does present an issue when using the Subsequence of array; ArraySlice. The first element of an ArraySlice will likely not have its first index as 0 (unless the subsequence is a prefix of an array) and trying to access that element will cause an ‘Index out of bounds’ fatal error.

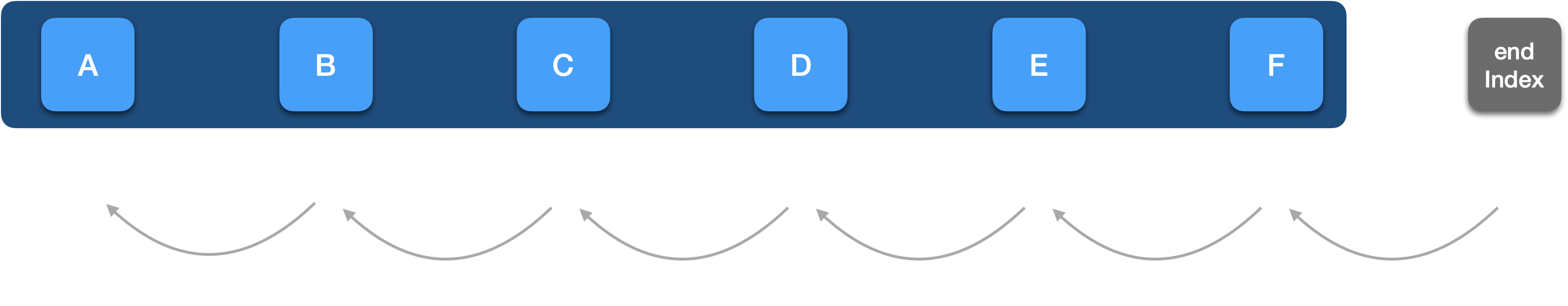

BidirectionalCollection

A BidirectionalCollection extends the Collection protocol to allow for efficient reversed iteration.

The protocol adds methods for getting the index before a specified index.

protocol BidirectionalCollection<Element>: Collection {

func index(before i: Self.Index) -> Self.Index

func formIndex(before i: inout Self.Index)

}

A Bidirectional collection gets a further optimisation via an overloaded reversed() method.

The implementation for Sequence and Collection both return a new array which contains all the elements in reverse order.

BidirectionalCollection instead returns a ReversedCollection object which wraps the original collection without having to allocate a new array of perform the reverse. This can then be efficiently iterated through.

RandomAccessCollection

A RandomAccessCollection extends from BidirectionalCollection but does not add any new methods or requirements for the collection (beyond its Indicies & SubSequence being required to also conform to RandomAccessCollection).

That it does expect, however, is that calculating the distances between and traversing the indices of the collection is an efficient, constant-time (O(1)) operation.

This can be either be done by having the Index type conform to the Stridable protocol which allows the distance to be calculated or by implementing the index(_:offsetBy:) and distance(from:to:) methods to allow for efficient, constant-time calculation.

MutableCollection

The MutableCollection protocol specifies that a collection is mutable by allowing the element at an index to be replaced. It does not mean that a collection is resizable, nor that an element be removed; effectively a mutable collection allows the elements at indices to be replaced but not necessarily that the indices of the collection can change.

RangeReplaceableCollection

A RangeReplaceableCollection protocol can be considered the opposite/compliment of MutableCollection. It allows a range of indices (and their elements) to be added, removed, or replaced but does not necessarily guarantee that those indices will still exist when replaced, so you cannot directly get replace the value at a specific index, you can only replace the elements at an index or range of indices with elements and the collection will determine what indices they will use.

So a question arises. Why does RangeReplaceableCollection not inherit from MutableCollection? Well, the answer is String.

String is a BidirectionalCollection which conforms to RangeReplaceableCollection but not MutableCollection.

The reason for this is that not all displayable characters are the same length.

| Character | UTF16 | Unicode Scalers |

|---|---|---|

| e | [101] | [“\u{0065}”] |

| é | [233] | [“\u{00E9}”] |

| 👨 | [55357, 56424] | [“\u{0001F468}”] |

| 👩 | [55357, 56425] | [“\u{0001F469}”] |

| 👦 | [55357, 56422] | [“\u{0001F466}”] |

| 👧 | [55357, 56423] | [“\u{0001F467}”] |

| 👨👩👦 | [55357, 56424, 8205, 55357, 56425, 8205, 55357, 56422] | [“\u{0001F468}”, “\u{200D}”, “\u{0001F469}”, “\u{200D}”, “\u{0001F466}”] |

| 👨👩👧 | [55357, 56424, 8205, 55357, 56425, 8205, 55357, 56423] | [“\u{0001F468}”, “\u{200D}”, “\u{0001F469}”, “\u{200D}”, “\u{0001F467}”] |

| 👨👩👧👦 | [55357, 56424, 8205, 55357, 56425, 8205, 55357, 56423, 8205, 55357, 56422] | [“\u{0001F468}”, “\u{200D}”, “\u{0001F469}”, “\u{200D}”, “\u{0001F467}”, “\u{200D}”, “\u{0001F466}”] |

In the later three emoji, you can see that they are actually composed of the individual face emojis above but joined by a “zero-width joiner” (\u{200D}) to make them into a single character.

This is also part of the reason why String does not use just an integer for its index. The position and size of a character can be widely different and the index is there for efficient access to that character.